Understanding Myelodysplastic Syndromes: A Patient Handbook

John M. Bennett, MD

Peter

Kouides is Associate Professor of Medicine,

University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry,

Strong Memorial Hospital, Rochester, New York.

John M.

Bennett is Professor of Oncology in Medicine,

Pathology, and Laboratory Medicine, University of

Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry.

Dr. Bennett is a member of the

University of Rochester Cancer Center.

Published by the Myelodysplastic Syndromes Foundation, Second Edition, revised, 2001.

![]()

WHAT IS MDS?

MDS, or the myelodysplastic syndromes, are a group of diseases of the bone marrow. Healthy bone

marrow produces immature blood cells that then develop into red blood cells, white blood cells,

and platelets. When MDS affects the normal development process, progenitor cells ("blasts") fail

to respond to normal control signals, resulting in a disproportionate number of these primitive

cells remaining in the bone marrow. Meanwhile, levels of the circulating, mature blood cells

fall. The mature blood cells, in addition to being fewer in number, may not function properly

due to dysplasia (misshapening).

Failure of the bone marrow to produce normal cells is a gradual process. Because the process is gradual and because MDS is primarily a disease of the aging-most patients are over 65 years old-it is not necessarily a terminal disease. However, some patients do succumb to the direct effects of the disease through loss of the ability to fight infections and control bleeding. In addition, for roughly 30% of the patients diagnosed with MDS, these diseases will progress to acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a type of bone marrow malignancy which does not respond well to chemotherapy. So while, in total, 70 to 75% of patients diagnosed with MDS eventually succumb to the direct effects of MDS or to AML, there is a group of patients for whom the onset of MDS will not result in a shortened life span.

![]()

EFFECT ON RED BLOOD

CELLS

The bone marrow produces red blood cells which, when mature, carry oxygen to the body's tissues.

The percentage of red blood cells in the total blood volume is called the hematocrit. In healthy

women, the hematocrit is 36 to 46% while in healthy men, the hematocrit is 40 to 52%. When the

hematocrit falls below the normal range, there is an insufficient number of red blood cells to

effectively supply oxygen throughout the body. This condition of low oxygen, called anemia, can

be relatively mild (hematocrit of 30 to 35%), moderate (25 to 30%), or severe (less than 25%).

Anemia can also result from the inefficient transport of oxygen by dysplastic (mature but

misshapen) red blood cells.

|

|

|

Normal red blood cells

|

Abnormal red blood cells

|

![]()

EFFECT ON WHITE BLOOD CELLS

The bone marrow also produces white blood cells, which both prevent and fight infection. The bone marrow normally makes between 4,000 and 10,000 white blood cells per microliter of blood; in African-Americans the range is lower, between 3,200 and 9,000 white blood cells per microliter. There are several types of white cells, including neutrophils (alternatively known as granulocytes) which primarily fight bacterial infections and lymphocytes which primarily fight viral infections.

Neutropenia, the term used to describe a low count of white blood cells, develops in most MDS patients. In these patients, it is usually the neutrophils which are in particularly short supply. Neutropenia elevates the risk of contracting bacterial infections such as pneumonia and urinary tract infections.

Some MDS patients who have not yet

developed neutropenia still suffer recurrent infections. Although the count is normal, white

blood cells are not able to function as well as those in a healthy person.

![]()

EFFECT ON PLATELETS

The bone marrow also produces platelets which are critical to blood coagulation, and thus cessation of bleeding. The bone marrow normally manufactures between 150,000 and 450,000 platelets per microliter of blood.

Most MDS patients develop a low platelet count, called thrombocytopenia. Severe thrombocytopenia, which is uncommon, is defined as a platelet count below 20,000. It is associated with numerous bleeding problems.

![]()

WHAT CAUSES MDS?

With a few exceptions, the exact causes are unknown. Some evidence suggests that certain people are born with a tendency to develop MDS. This tendency can be thought of as a switch that is triggered by an external factor. If the external factor cannot be identified, then the disease is referred to as "primary MDS".

Radiation and chemotherapy are among the known triggers. Patients taking chemotherapy drugs for potentially curable cancers, such as Hodgkin's disease and lymphoma, are at risk of developing MDS for up to ten years following treatment. MDS triggered by chemotherapy agents, called "secondary MDS," is usually associated with multiple chromosome abnormalities in the bone marrow. This type of MDS often develops rapidly into AML.

Exposure to certain environmental chemicals can also trigger MDS. Unfortunately, it is not clear which chemicals, aside from benzene, are implicated.

There are no known food or agricultural products that cause MDS. While alcohol consumed on a daily basis may lower red blood cell and platelet counts, alcohol does not cause MDS. As for tobacco, insufficient data are available to determine if smoking increases the risk of developing MDS. It is known, however, that the risk of developing AML is 1.6 times greater for smokers than for non-smokers.

Patients and their families often worry that MDS might be contagious. There is no evidence to suggest that MDS is caused by a virus, thus MDS cannot be transmitted to loved ones. Because they are not at increased risk of developing MDS, family members do not need to have routine blood counts. In fact, it is a very rare occasion when siblings are diagnosed with MDS.

![]()

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS OF MDS?

Many patients in the early stages of MDS experience no symptoms at all. In this case, a routine blood test will reveal a reduced red cell count, or hematocrit, sometimes along with reduced white cell and/or platelet counts. On occasion, the white cell and platelet counts may be low while the hematocrit remains normal. In any case, when the disease is in its early stages, the counts are not so reduced as to necessarily produce symptoms.

Other patients, particularly those with greater reductions of cell counts, experience definite symptoms. These symptoms depend on which blood cell type is involved as well as the level to which the cell count drops. The symptoms are described below.

Low red cell count

(anemia)

Anemic patients experience fatigue

and related symptoms. In mild anemia (hematocrit of 30 to 35%), the patient may feel well or

just slightly fatigued. In moderate anemia (hematocrit of 25 to 30%), almost all patients

experience some fatigue which may be accompanied by heart palpitations, shortness of breath, and

pale skin. In severe anemia (hematocrit of less than 25%), almost all patients appear pale and

suffer severe fatigue and shortness of breath. Because severe anemia reduces blood flow to the

heart, older patients may suffer chest pains (angina) or have a heart attack.

Low white cell count (neutropenia)

A reduced white cell count lowers resistance to bacterial infection. Patients with neutropenia

may be susceptible to skin infections, sinus infections (symptoms include nasal congestion),

lung infections (symptoms include cough, shortness of breath), or urinary tract infections

(symptoms include painful and frequent urination). Fever may accompany these infections.

Low platelet count

(thrombocytopenia)

Patients with thrombocytopenia have an increased tendency to bruise and bleed, even after minor

bumps and scrapes. Bruises can be dramatic, some as large as the palm of the hand. Nosebleeds

are common and patients often experience bleeding of the gums, particularly after dental work.

Before having dental work, advance consultation with the hematologist, who may prescribe the

prophylactic use of antibiotic, is recommended since infection and bleeding pose greater risks

for most MDS patients.

![]()

WHAT TESTS ARE USED TO DIAGNOSE MDS?

BLOOD TESTS

The initial step towards diagnosis is to have blood drawn from the arm; the blood sample is then

evaluated for cell counts (red blood cells, white blood cells and their subtypes, and

platelets), shape and size of the red blood cells, and the level of erythropoietin (EPO). EPO is

a protein, produced by the kidneys in response to low oxygen in body tissues, that stimulates

the production of red blood cells in the bone marrow.

If the blood test indicates that the red blood cells are misshapen, the patient could possibly have a Vitamin B12 or folate deficiency. Like MDS and AML, these vitamin deficiencies result in dysplasia (misshapening) of the red blood cells, making these cells less efficient in transporting oxygen. To rule out Vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies as the cause of anemia, levels of these vitamins in the blood will also need to be measured.

BONE MARROW EXAMINATION

BONE MARROW EXAMINATION

If the blood test indicates a low

hematocrit, possibly along with a low white cell and/or platelet count, a bone marrow

examination is performed. The bone marrow is examined for 1) the percentages of blasts and

abnormal, mature blood cells, 2) iron content of the red blood cells, and 3) abnormalities the

chromosomes (cytogenetic findings), such as as missing or extra chromo-somes. Periodic bone

marrow exams are also used to determine if MDS has transformed to AML.

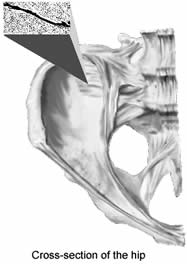

Procedure Used in the Bone Marrow Examination

This procedure can be performed in the physician's office and it usually takes about twenty

minutes. A mild sedative or narcotic may be given to the patient. The patient then reclines on

the examining table, on either the stomach or the side, preferably whichever way is most

comfortable. The physician feels for the bony protrusion on the right or left back side of the

hip, known as the posterior iliac crest; this site, and not the spine, is the location used for

the bone marrow examination of MDS patients. The physician swabs the skin with iodine and places

a sterile towel and drape over the area to reduce the risk of bacterial infection.

A needle, smaller than one used to draw blood from the arm, is slowly inserted under the skin to inject the local anesthetic lidocaine. The patient may feel a twinge of pain but, soon, a dime-sized area of the skin is numb. Next, a longer, slightly larger needle is used to inject anesthetic into the bone itself. It is common for patients to experience a twinge of pain when the second needle is inserted. Once the needle makes contact with the bone, the patient should only feel a slight pressure, as though a thumb were pressing against the skin.

After about five minutes, the bone covering, or periosteum, should be well anesthetized. If, however, the patient continues to have sensation, additional lidocaine is injected into the area. Afterwards, the physician proceeds with a third, larger needle, which is inserted into the bone marrow. (Since there are no nerve endings in the marrow, this stage should be painless.) While asking the patient to take several slow, deep breaths, the physician attaches a syringe to the end of the needle and then quickly pulls out, or aspirates, the marrow, removing about a tablespoon in quantity. Typically the patient experiences a shock-like sensation during this part of the procedure but just for a fraction of a second. Often a second aspiration is done to obtain additional marrow for evaluation of both the percentage of blast cells and for cytogenetic testing.

Finally, a fourth, wider needle is inserted to obtain a narrow (several-millimeter diameter) core of the bone for biopsy. As the needle is being inserted into the bone, the patient should feel nothing more than dull pressure. When the physician loosens the bone and removes it, the patient experiences a jerking sensation. The bone marrow extraction is over, and the patient is readied for departure. For safety reasons, the patient should have another person available to be the driver.

Risks of a Bone Marrow

Examination

The exam carries three risks: infection, bruising and bleeding, and discomfort. Regarding

infection, anytime a needle is inserted through the skin there is the possibility of infection.

However, it is highly unlikely to occur if antiseptic conditions are maintained throughout the

procedure.

After the examination, some patients develop a sizable bruise or a swelling of blood (hematoma) under the skin, particularly those whose platelet count is low. If the platelet count is below 50,000 platelets per microliter, the physician will apply at least five minutes of pressure over the needle site.

Discomfort is a common fear of patients who face a bone marrow examination. It might help reduce fear to point out that a bone marrow examination is similar to a tooth being pulled. In each case, the bone is "pricked." If this is properly done, there should be little pain other than the twinge of the needle going under the skin.

Some patients express a preference for general anesthesia. General anesthesia has its own risks, however, and is not necessary for conduct of a bone marrow exam. If the patient remains concerned that a local anesthetic will not be adequate, additional medication may be requested.

![]()

HOW SEVERE IS MY MDS?

Currently, two scoring systems are used to describe the type or aggressiveness of MDS and the

prognosis for the patient: the French-American-British (FAB) classification system and the

International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS).

![]()

FRENCH-AMERICAN-BRITISH (FAB) CLASSIFICATION

The FAB Classification was developed in the early 1980s by a group of physicians from France,

the United States, and Great Britain. The central criterion for classification in the FAB system

is the percentage of blast cells in the marrow, with less than 2% blasts considered normal for

healthy bone marrow. The five categories of the FAB classification are described below.

Refractory anemia (RA). Patients are not responsive, that is, refractory, to iron or vitamins. There may be mild to moderate thrombocytopenia and neutropenia, with less than 5% blasts observed in the bone marrow. Less than 10% of patients having refractory anemia develop AML. Median survival of patients with refractory anemia is about 4 years.

Refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts (RARS). Sideroblasts are red blood cells containing granules of iron; ringed sideroblasts are abnormal. In patients with this disorder, less than 5% of marrow cells are blasts. Less than 5% of the patients having refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts develop AML. The median survival of this group of patients is 55 months.

Refractory anemia with excess blasts (RAEB). Five to 20% of the marrow cells are blasts, and the circulating blood also contains 1 to 5% blasts. Of the patients having refractory anemia with excess blasts, 20 to 30% develop AML. Median survival for patients in this group is about 2 years.

Refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation (RAEB-t). Twenty to 30% of the marrow cells are blasts, and more than 5% blasts are found in the bloodstream. Seventy-five percent of these patients develop AML. In fact, some experts believe that patients in this MDS group should instead be classified as having a form of AML; so classified, these patients would have access to treatments approved for AML but not yet approved for treatment of MDS. Median survival for patients having refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation is about 6 months.

Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML). The marrow contains 1 to 20% blasts and there is also an increase in blood and marrow monocytes, the white blood cells which remove dead, injured, or cancerous cells. This type of leukemia should be distinguished from chronic granulocyte leukemia. Median survival of patients having CMML is about 3 years.

![]()

INTERNATIONAL

PROGNOSTIC SCORING SYSTEM (IPSS)

A more recently developed system for grading the severity of MDS is the International Prognostic

Scoring System. Following a patient's evaluation, the disease is "scored" in terms of the risk

to the patient, that is, shortened life expectancy and the chances of transformation of the

disease to AML. The IPSS Score is a function of the percentage of blasts appearing in the bone

marrow, the cytogenetic finding (identification of chromosomal abnormalities) in bone marrow

blood cells, and the blood cell counts and other blood test findings.

|

Determining the IPSS Score

|

|

|

.

|

Score Value |

|

Blasts

|

. |

|

5% or less

|

0.0 |

|

5-10%

|

0.5 |

|

11-20%

|

1.5 |

|

21-30%*

|

2.0 |

|

Cytogenetic Finding**

|

. |

|

Good

|

0.0 |

|

Intermediate

|

0.5 |

|

Poor

|

1.0 |

|

Blood-Test Findings***

|

. |

|

0 or 1 of the findings

|

0.0 |

|

2 or 3 of the findings

|

0.5 |

|

IPSS Score: Total of individual

score values for blasts, cytogenetic finding, and blood-test findings.

|

|

| * Patients whose marrow contains more than 30% blasts have acute myeloid leukemia. | |

| ** "Good": normal set of 23 pairs of chromosomes, or a set having only partial loss of the long arm of chromosomes #5 or #20, or loss of the Y chromosome. | |

| "Intermediate": Other than "Good" or "Poor" | |

| "Poor": Loss of one of the two ("monosomy") #7 chromosomes, addition of a third ("trisomy") #8 chromosome, or three or more total abnormalities. | |

| *** Blood-Test Findings defined as: Neutrophils <1,800 per microliter; Hematocrit <36% of red blood cells in total body volume; Platelets <100,000 per microliter | |

The IPSS Score, as determined by the summation of the individual score values for the percentage of blasts and for the cytogenetic and blood test findings, is used to assess the clinical outcome for the MDS patient. The IPSS Score indicates which of the following risk groups a patient falls into:

Low-Risk Group: IPSS

Score of 0.

Approximately 50% of patients will survive 5.7 years. Twenty-five percent of patients will

develop AML within 9.4 years.

Intermediate-Risk Group

I: IPSS Score of 0.5 to 1.0.

Approximately 50% of patients will survive 3.5 years.

Twenty-five percent of patients will develop AML within 3.3 years.

Approximately 50% of patients will survive 3.5 years.

Twenty-five percent of patients will develop AML within 3.3 years.

Intermediate-Risk Group

II: IPSS Score of 1.5 to 2.0.

Approximately 50% of patients will survive a year. Twenty-five percent of patients will develop

AML within a year.

High-Risk Group: IPSS

Score over 2.0.

Approximately 50% of patients will survive 4.5 months. Seventy-five percent will develop AML.

The physician will review the data collected from the blood tests and bone marrow examination as well as the classifications (FAB and/or IPSS) of these data in terms of the severity of the disease. (Use the boxed "Table of Test Results and Disease Severity" to record personal data.) The treatment program then recommended by the physician will depend upon the degree to which blood parameters are reduced and the risk of progression to AML.

|

Table of Test Results and

Disease Severity

|

||

|

Parameter (units)

|

Normal Result

|

My Result

|

|

Hematocrit (% red cells in blood)

|

36-52%

|

_________

|

|

White cell count (cells/?l blood)

|

3,200-10,000

|

_________

|

|

Platelet count (platelets/?l blood)

|

150,000-450,000

|

_________

|

|

Serum erythropoietin level (IU/L)

|

10-20

|

_________

|

|

Blast frequency (% of bone marrow

cells)

|

<2%

|

_________

|

|

Cytogenetic finding* (Good,

Intermediate, Poor)

|

Good

|

_________

|

|

FAB classification

|

Not applicable

|

_________

|

|

IPSS classification

|

Not applicable

|

_________

|

|

Vitamin B12 and/or folate deficiencies

(No, Yes)

|

No

|

_________

|

|

*See footnotes to table "Determining

the IPSS Score"

|

||

![]()

HOW IS MDS TREATED?

The possible treatments, used alone or in combination, include: 1) supportive care via

transfusions, antibiotics, and other medications, 2) stimulation of normal progenitor cells

through administration of growth factors, and 3) removal of abnormal progenitor cells through

chemotherapy and, perhaps, replacement with healthy tissue via bone marrow transplantation.

Promising new treatments are also under study.

![]()

EARLY STAGES OF MDS

Treatment of Anemia

Although the number of successes has been limited for the first three treatments listed below,

anemic patients in the IPSS Low-Risk Group or Intermediate-Risk Group I may gain some benefit

from the following treatments and, in particular, from transfusion of red blood cells.

Erythropoietin (EPO). This growth factor stimulates the bone marrow to produce red blood cells. When EPO is injected under the skin (subcutaneously) three to seven times a week, the red cell count increases for 30% of the EPO-treated patients. The treatment is most helpful and, at roughly $500/week, most cost-effective, when the patient's natural (blood serum) EPO level is below 200 IU/L (International Units per liter). Some patients may derive additional benefit when EPO is combined with the white cell growth factors known as G-CSF and GM-CSF (discussed later).

Pyridoxine (Vitamin B6). If the bone marrow stain shows deposits of iron in the red cells, indicating sideroblastic anemia, then the patient might try taking 100 mg of pyridoxine twice a day. Insufficient levels of pyridoxine, which may be a side-effect of certain drugs, may be hereditary, or may result from poor absorption of the vitamin from food, will impede the body's use of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins that are essential to cell structure and function. Pyridoxine therapy can relieve sideroblastic anemia through increases in red cell counts for about 5% of MDS patients. As a caution, pyridoxine doses exceeding 100 mg twice daily can produce side effects such as tingling of the fingers.

Desferal? (Deferoxamine).

Some patients with sideroblastic anemia will improve upon use of Desferal. This medication

chelates, or binds, with iron in such a way that the body can more effectively remove the excess

iron. Removal of excess iron, a strong oxidant, will help to protect body tissues from damage

and additional disease. Desferal treatment is particularly important for management of iron

overload as a result of red cell transfusions (see below). Desferal is usually administered

intravenously throughout the night using a portable, battery-operated pump.

Red Cell Transfusions. A patient in the IPSS Low-Risk Group or Intermediate-Risk Group I who is not producing enough red blood cells may be given a transfusion of red blood cells. Patients who are quite anemic (hematocrit consistently less than 25%) receive periodic transfusions, typically two units every 2 to 6 weeks.

There are several issues or concerns related to red cell transfusions. First, as a result of frequent transfusions, older patients have some risk of retaining excess fluid which then cause shortness of breath. Fortunately, the fluid build-up can usually be managed by intravenous administration of the diuretic Lasix?. Second, all patients have a risk of accumulating iron. Besides other effects, excess iron deposits on the heart and liver which, as a result, can shorten life expectancy. Desferal (discussed above), administered through a pump nightly, can help to lower the iron level. Third, transmittal of viruses through transfusion is often a concern. However, tests conducted on donated blood provide for detection of certain viruses, making the risk of transmittal very low. For instance, the chance of contracting HIV is 1 in 500,000 transfusions; of contracting hepatitis C, 1 in 100,000; and of contracting hepatitis B, 1 in 60,000. Much higher are the risks run by avoiding transfusion treatment when it is needed.

![]()

TREATMENT OF NEUTROPENIA

White Cell Growth Factors. If a patient has a low white cell count and has experienced at least one infection, administration of white cell growth factors are an option. Two growth factors, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), are administered under the skin between one and seven times a week. Seventy-five percent of the patients who use G-CSF (Neupogen?; filgrastim) or GM-CSF (Leukine?; sargramostim), experience increased white cell production which, in turn, may help to reduce the likelihood of additional infection. Neupogen and Leukine do not cause major side effects, with patients only occasionally reporting rashes and bone pain. These medications, however, have not been shown to prolong survival.

White Cell Transfusions. Because white cells are not as amenable to transfusion, supportive care consists primarily of the administration of antibiotics.

![]()

TREATMENT OF THROMBOCYTOPENIA

Platelet Growth Factors. At present, there is no growth-factor medication for patients having thrombocytopenia. On-going studies, however, are showing promising results: platelet counts may increase through treatment with growth factor medications such as Interleukin-11, Interleukin-6, and in particular, thrombopoietin.

Platelet Transfusions. Platelet transfusions are rarely given unless the platelet count is below 10,000 per microliter of blood (with normal counts ranging from 150,000 to 450,000). Patients will eventually become resistant to the transfused platelets, so transfusions of new platelets would periodically be necessary.

![]()

ADVANCED STAGES OF MDS

Induction Chemotherapy

Patients whose MDS has been classified as belonging to the IPSS High-Risk Group and the

Intermediate-Risk Group II have a high probability of the MDS progressing to AML. For this

reason, these patients should consider receiving intravenous chemotherapy which, as relatively

strong doses, may "induce" control of the MDS by killing the myelodysplastic cells.

Importantly, chemotherapy treatment has significant side-effects. Commonly recognized side effects include hair loss and development of mouth sores and diarrhea. But besides these effects, chemotherapy adversely affects healthy cells along with the myelodysplastic cells. Because of the loss of normal blood cells, the patient remains hospitalized for several weeks following chemotherapy while transfusions of red cells and platelets are given along with antibiotics to fight infection. If the induction chemotherapy adequately controls the myelodysplastic cells, then relatively normal blood cells should again grow within several weeks. As normal cells proliferate, the frequency of transfusion will decrease and the risk of infection will lessen.

Unfortunately, the chance of controlling MDS with induction chemotherapy is only about 30%. Even in successful cases, the disease often returns within twelve months. Thus, aggressive chemotherapy is given to a minority of MDS patients.

![]()

Bone Marrow

Transplantation

Bone marrow transplantation is potentially a very effective treatment, possibly even a cure,

however it is also very risky and requires donation of matched marrow. To match, the marrow must

be donated by a sibling (or, on a very rare occasion by a matched unrelated donor) and must be

of the same transplantation type; matching of transplantation type, which is determined through

a blood test, should not be confused with matching of blood type. More specifically, the cells

of the donor must have the same human leukocyte antigens (HLA) as those of the recipient.

Antigens, which are found on surfaces of every cell, detect foreign material and then initiate

an immune response. Thus, matching HLA is critical to preventing rejection of the transplanted

tissue. Unfortunately, HLA of children and parents are not sufficiently similar to qualify as a

match.

Besides the risk of rejection from insufficiently-matched HLA, there are other risks. The patient's liver or lungs may become damaged and there is the ever-present risk of infection. In addition, the transplanted bone marrow (graft) could reject the patient (host), which is known as graft-versus-host disease. In this case, it is the white blood cells from the donated marrow which attack the patient's tissues.

All together, complications associated with standard bone marrow transplantation result in the death of 30 to 50% of the treated patients within one year following the procedure. Any potential gain in survival time is usually not considered worth the risk for most MDS patients as this is a disease which typically develops late in life. Therefore, patients over 60 usually do not undergo bone marrow transplants. The decision for younger patients, especially those with additional medical issues, is more difficult.

To date, about 500 MDS patients have undergone bone marrow transplantation and almost all have been under the age of 40. Patients who survive the complications have a good chance of being cured.

The objective of the procedure is to replace all myelodysplastic cells with normal cells. This is accomplished by using chemotherapy to kill the patient's marrow and blood cells and then injecting donated marrow into the patient's veins, the donated marrow having been removed by syringe from the hip bone of a donor who is under general anesthesia. Once injected into the recipient patient, the marrow travels to the bones then begins to reproduce and, given there are no complications, will take over the functions of the original marrow.

"Mini" transplants, a recent area of investigation, may provide another option for the older patient with access to matching marrow. Mini-transplants utilize a lower dose of chemotherapy to destroy most or all of the myelodysplastic cells. The lower dose is better tolerated by older patients, thus the patient will suffer fewer side effects of the chemotherapy and, being stronger, may have a greater chance of surviving the transplant. (Younger patients, who generally are more vigorous, should receive that standard dose of chemotherapy to ensure that all myelodysplastic cells have been killed.) Studies of mini-transplants for patients 55 to 70 years old are in progress.

![]()

OTHER THERAPIES

VITAMIN THERAPY

Vitamins have been an active area of MDS research over the past two decades. In test tubes,

myelodysplastic cells often normalize when exposed to vitamins such as D3 and A (retinoic acid).

Overall, however, clinical trials have been disappointing. Presently a major area of research is

devoted to combining vitamins with low doses of chemotherapy and/or growth factors such as EPO

and GM-CSF. It may be worth asking your specialist about any on-going studies.

EXPERIMENTAL THERAPIES

Other therapeutic agents, while not yet having received full governmental approvals for

treatment of MDS, may be available through clinical trials. These new agents include:

Amifostine (Ethyol?). For some patients, administration of amifostine three times a week intravenously may stimulate maturation of blood cells, thereby improving blood cell counts and decreasing the percentage of blast cells located in the bone marrow. Benefits are only derived when the patient is currently receiving this treatment. Further, additional study is needed to determine if lower doses will provide some benefit while minimizing associated side effects.

Topotecan (Hycamtin?). Administered intravenously and orally, without or with other chemotherapy drugs (for example, cytosine arabinoside, also known as Ara-C), topotecan has resulted in complete remission of MDS in some patients. However, the duration of remission is not long as these patients experience continuous relapses with no apparent change in survival time. Side effects associated with topotecan are generally manageable.

Melphalan (Alkeran?).

Low doses of this chemotherapy drug have resulted in remission or partial remission of the

disease for limited duration.

5-azacytidine and decitabine. These chemotherapy agents act on repressed genes to allow for

normal functioning of the genetic code. The potential benefit of these treatments is an increase

in all three types of blood cells.

Thalidomide (Thalomid?) and anti-vascular endothelial growth factors (anti-VEGF). MDS and leukemia patients have elevated levels of vascular endothelial growth factors and angiogenic factors; together, these factors increase the number of blood vessels and the growth, distribution and formation of solid tumors. Thalidomide and anti-VEGF reduce the blood supply in the marrow, thereby working against the adversely elevated levels of these growth factors.

Mylotarg?. This medication is used as a follow-up to bone marrow transplants and is currently approved for treatment of AML. Mylotarg is a chemotherapy drug which is conjugated, or attached, to antibodies. The antibodies bind specifically to antigens, or surface protein, of the primitive leukemegenic cells. Thus, the drug is targeted to the bone marrow blast cells from which the dysplastic cells develop so toxicity to nontarget cells is kept at a minimum. Mylotarg will also be tested in MDS patients.

![]()

CONCLUSION

MDS is a puzzling, life-threatening set of disorders for which there are no easy cures or quick remedies. Treatment consists largely of supportive care. While more aggressive therapies, such as chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation, may be options, these treatments can sometimes do more harm than good. It is, therefore, incumbent upon both patient and physician to be cautious in considering the level and type of treatment provided. Whatever path is ultimately chosen, above all it should reflect the patient's preferences.

- Alkeran is a trademark of GlaxoSmithKline.

- Desferal is a trademark of Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation.

- Ethyol is a trademark of Alza Pharmaceuticals.

- Hycamtin is a trademark of GlaxoSmithKline.

- Lasix is a trademark of Aventis Pharmaceuticals.

- Leukine is a trademark of Immunex C.

For further information contact:

The MDS Foundation

PO Box 353

36 Front Street

Crosswicks, NJ 08515Within the US Tel: 1-800-MDS-0839

Outside the US Tel: 1-609-298-6746

Fax: 1-609-298-0590Kathy Heptinstall , Operating Director